About عن

CrossRoads: European cultural diplomacy and Arab Christians in Palestine. A connected history during the formative years of the Middle East.

This project aims to revisit the relationship between the European cultural agenda and the local identity formation process, and social and religious transformations of Arab Christian communities in Palestine, when the British ruled via the Mandate. What was the role of culture in European policies regarding the Arabs of Palestine? How did Arab Christians use culture to define their place in the proto-national and religious configuration between 1920 and 1950?

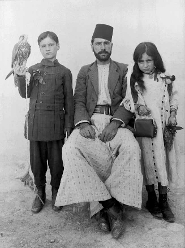

Chauffeur, Nablus – F. Scholten

This project proposes a connected history of the Arab Christian communities in Palestine during the formative years of the Middle East (1920-1950) and the birth of the cultural diplomacy via an interdisciplinary and entangled approach, relying on mainly unpublished sources. It will investigate the relationship between the European cultural agenda and the local identity formation process, and social and religious transformations of Arab Christian communities in Palestine.

Questions الأسئلة

What was the role of culture in European policies regarding the Arabs of Palestine? How did Arab Christians use culture to define their place in the proto-national and religious configuration between 1920 and 1950? This project begins with the assumption that the history of Arab Christianity must be studied in the wider context of European and global developments, and via its cultural elements.

Hypothesis فرضية

1. Mandate authorities addressed Muslim and Jewish communities (via legal frameworks, proto-national agenda, sectarian policies) but not Christian communities, leaving them somewhat apart. One result was that they over-proportionally invested in culture as a cornerstone of their identity.

2. Palestine was a nexus of cultural milieus (European actors and Jewish immigrants). Their culture played a major role in the construction of the Jewish nation and this process impacted the Arab Christian communities’ sense of ‘cultural promotion’.

3. Following WWI, international relations were becoming inexorably linked to political ideology and rivalry between European states took on a cultural component.

4. Supranational religious actors (Vatican, Orthodox Patriarchates) promoted diverse linguistic and cultural agendas by investing in cultural associations.

These hypotheses will be answered via a close study of the three main actors: the two most numerous indigenous Christian populations, the Orthodox and the Melkite (Greek Catholic), and the European cultural actors. The project will analyse the cultural practices and ideas of the two main Christian communities of Palestine (Orthodox and Melkites), their communal and religious leaders (foreign and local), and their interactions with different European cultural actors and early diplomacy (cultural, regional and global perspective). Practices and perceptions of culture of both Orthodox Christians and Melkites changed drastically during the Mandate. Many cultural clubs appeared at the beginning of the 1920s (literary, athletic, political committees), shifting towards more communal cultural associations in the 1930s. At the same time, different European countries used culture as a tool of influence in the Arab world.

In this project, the perspective on culture will be that of historical discourse rather than that of culture as a product or an object (P. Burke, W. Frijhoff). Recent developments in the Middle East have brought religious difference back to the attention of the scholarly world, questioning the numerous differences beneath the notion of nationalistic Arab unity and the role of culture. Culture provides a powerful tool to analyse the connected history of Arab Christians with Europe. The cultural spectrum reveals, on the contrary, a rich diversity of Arab Christianity and allows us to explore it ‘from within and without’ during this formative period for the Middle East with two political transitions (the British Mandate and the creation of Israel).

Twin Globe Trotters,

Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem – F. Scholten

Subproject 1:

Between the Holy Land and the World: the Melkite community of Palestine

Nowhere in the Middle East was the influence of western religious educators as large as in the Palestine, originating in the nineteenth century and increasing substantially during the British Mandate (Murre-van den Berg 2006). The Melkite community had special links with the French who were in charge of their religious training (St Anne seminary in Jerusalem). The majority of Melkites cultivated close contacts with Syria and Lebanon (central for their hierarchy) and participated in cultural associations active beyond the borders of Palestine.

Melkite leaders seemed to have carefully considered benefits and drawbacks of both cultural backgrounds (Arab and Western cultures) internally, while continuing to enhance their Arab culture and language, to advocate for Palestine, for the Arab Christianity and for their own community outside Palestine, promoting a variant of national identity that would incorporate both cultures.

They played a key role in Rome after the creation of the Pontifical Institute and the Holy Congregation for the Oriental Churches in 1917, where leading figures were successfully advocating for a deeper comprehension and actions from the Holy See towards Arab Christianity, promoting the recognition of its specific culture (Card. Tisserand, C. Korolevskij).

At the same time, Melkite leaders emphasised the links between their Church and the ‘Palestinian Fatherland’, and communal and Vatican secret archives reveal the close relation between the bishop of Akka, G. Haggear, and the Grand Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husayni. From cross-archival work emerges their complex mechanism to mobilize beyond Palestine (and including in Europe), using cultural nationalism as a vector.

How did the Melkite hierarchy and population react to the mixture of two cultures as an affirmation of their local roots and source of nationalism? What was the role of the Melkites in the elaboration of the Holy See’s views of Arabs after WWI?

Subproject 2:

Between the Holy Land and the Mediterranean: the Arab Orthodox community of Palestine

The Arab orthodox community was special in its consciousness of its indigenous character since the late XIXth century (Tamari 2014). During the Mandate, Arab Orthodox leaders maintained strong affinities with their Muslim fellows and worked to enhance the consciousness of Arab history and culture as basis for Arab nationalism. When the nationalist Arab movement became defined increasingly by Islam, Arab Orthodox leaders debated and fought that shift. During the final decade of British administration, Orthodox associations promoted an exclusively Christian Arab nationalism by proposing activities such as aid and educational opportunities, and establishing cultural centres.

This orthodox belief in a cultural indigenous character was shared by the Greek hierarchy, based on their perceived continuous local presence since byzantine times. The ethnic battle with the Greek hierarchy (originating typically from Greece) (Papasthatis 2013) was also fought via cultural debates, and resulted in complex self-reflections (particularly useful for this project).

The ‘nationalization’ process of the Orthodox institutions (gradual transformation of the organization of the Orthodox Church from a non-ethnic religious ‘representation’ to a national based religious affiliation) was accompanied by fierce and enlighteningcultural debates until WWII, fragmenting the previously ‘oecumenical Orthodoxy’ into ethnic-based religious entities.

How did the different Greek religious institutions address the cultural issues at stake with the Arab populations? How did Arab Orthodox elites promote culture to affirm their role in the Orthodox communal life in the Holy Land? What were the consequences on their relations with the Arab Catholic population?

This sub-project also aims to elaborate on transnational Orthodox links between the Levant and the Balkan and Slavic worlds. This includes the history of the ethnically Greek community in Jerusalem as well as comparisons of cultural Arab Orthodox cultural production in Palestine with Greece and Russia.

Research on the Greek diaspora in Palestine will focus on the development of the Greek Colony, having as its centre the so-called Greek Club, as well as the role of Greek cultural diplomacy in its development. This research addresses the following themes: a) the establishment and development of the Jerusalem Greek diaspora; b) its relation to the Greek state; and c) its links to the Orthodox Patriarchate.

Research on cultural production focuses on two main areas. The first is the ways in which secular and modern painting practices developed from practices of iconography, paralleling the rise of nationalisms related to Orthodoxy. The second looks at specifically at Christian Arab cultural production for tourist-pilgrim markets and considers bottom up modes of cultural diplomacy from individual agents within the Palestinian art market.

Subproject 3:

Europe talking to the Levant

External linguistic and cultural policies are far vaguer than internal ones (presented as a cement of nations) and constitute a complex form of influence (Sanchez & Frijhoff 2016). The creation of institutions such as the British Council, the French Cultural Centre and the Italian Dante Society in Palestine was a sign of the emergence of a new type of foreign policy that later became systematic. European languages were at the heart of the first ‘cultural diplomacy’ in the 1930’s, inheriting elements of the XIXth century missionary presence, but evolving quickly into more complex forms of influence.

Cultural activities took place alongside dramatic political events and within the particular economic and religious circumstances of the period. Not surprisingly, the Arab culture was imbued with political issues and a developing sense of nationalism.

What cultural and ideological backgrounds did European representatives use when promoting their culture and language use? What was their role in the creation of or the opposition to sectarianism in Palestine? How did the Arab Christians use the European cultural agenda in their national and communal affiliations?